I once led a team tasked with designing a solution where users could purchase a vehicle online. The feature we were designing was a relatively innovative idea at the time, and there was a push by stakeholders to make it more difficult to find some of the critical financial information that customers needed to help them make a truly educated decision about their purchase.

The Dark Side of Design

My design team was told that we needed to show (but really hide) the massive APR hikes, extensive loan terms, and even the ancillary costs associated with such a major purchase deep within the user interface—a practice known in the industry as a “dark pattern.” The primary target audience of this company was typically minorities, with limited income or poor credit histories, and often, they were making this purchase for the first time with little experience in knowing what to look for when making such a large purchase.

Rather than seizing the opportunity to inform and educate these customers, I felt as though my team was being forced to manipulate the design to capitalize on the customer’s lack of understanding, resulting in users ultimately being burdened by a loan they will most likely never be able to financially recover from. In my mind, this practice felt highly unethical, disguised by a phrase that was said a lot around the office: “We’re doing them a favor by crediting them when no one else would.”

My realization that I was perpetuating “the dark side” of design prompted a career shift towards educating future design graduates about recognizing and avoiding manipulative design strategies and addressing bias in design by helping students obtain positive impact design careers. Designers rarely work alone and therefore don’t have complete control over the outcome of a product—but we can heavily influence and advise stakeholders down the right path.

Design by Definition

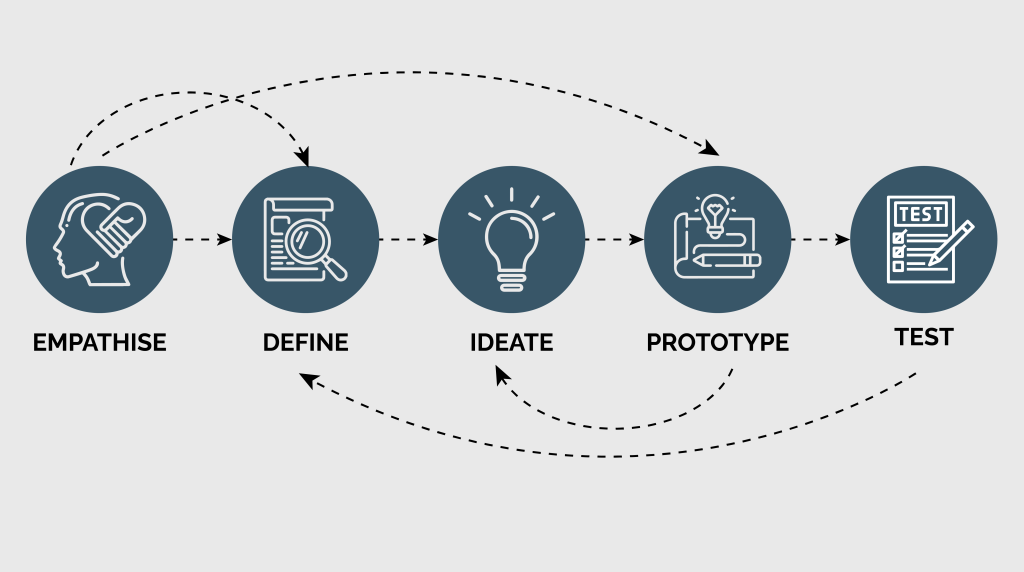

We create purpose-driven design by defining the things we make. Sarah Laoyan, writing for Asana, put it best: “The design thinking process is a methodology that helps tackle complex problems by framing the issue in a human-centric way.”

In other words: designers solve problems, and that process is rarely linear. But it’s important to think about the problem we’re solving and the impact that any solution may have on those we’re solving the problem for.

As designers, we confront dozens, if not hundreds, of possible solutions for every problem. The challenges we face are as diverse as the problems our clients and stakeholders present. However, designers must remember that every potential design solution acts on the physical world and should address a real human need. The minute designers forget those two things, a myriad of outcomes could occur—generally with negative results.

Source: Neha Siddiqa

Avoiding Bias In Design

Bias in design presents a significant hurdle in the process of ideation and creative thinking. All humans, including designers, are subject to unconscious bias, and it’s far easier to detect bias in others than it is to detect it within ourselves. These biases create perceptual blind spots. Standard linear thinking practices subtly influence our steps toward problem-solving, even though these practices may appear logical and unbiased.

Even methodologies like design thinking, which encourage open-mindedness, are not immune to the initial challenge of inherent biases that can skew our perspectives and ultimately make their way into the solutions we craft. Design as an industry is highly subjective and poses large opportunities for bias to run amuck, and as we venture into new, innovative territories in purpose-driven design with Artificial Intelligence (AI), Virtual Reality (VR), plus increasingly more sentient design solutions, maintaining an objective standpoint becomes increasingly more important.

Bias is not harmless

Biased design decisions can have far-reaching and often detrimental effects. A notable example is the case of facial recognition technology. Numerous studies, including one by the MIT Media Lab grad student Joy Buolamwini in 2018, revealed significant racial and gender biases in these systems. A dataset consisting mostly of lighter-skinned individuals biased the technology, leading it to misidentify people with darker skin tones, especially dark-skinned women, at significantly higher rates. This bias led to wrongful accusations and arrests, demonstrating a profound lack of equity in technological design and ultimately the application and end-use of that design. The repercussions extend far beyond mere inconvenience, affecting individuals’ lives and freedoms, and exposing deep-seated biases in the tech algorithms.

Additionally, a study in the Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association in 2019 found that many online health resources were not designed with elderly users in mind, employing small font sizes and complex navigation structures. This oversight effectively alienated a significant portion of their target audience—older adults relying on these resources for critical health information. The lack of consideration for the aging population’s needs in digital design hindered access to important health information and perpetuated a form of ageism.

It’s important to note that we can never completely eradicate bias, but understanding bias will go a long way toward revealing our blind spots. And being hyperconscious of it will also reduce the likelihood of our work causing unintentional harm through more purpose-driven design solutions. We have an increasing need for inclusive and unbiased design practices, which necessitates students and working designers alike to consider the positive impact design careers can have.

Tips for avoiding bias in design

- Self-awareness: Acknowledge you have biases, and consider taking an unconscious bias test. Total Brain offers a non-conscious bias test free of cost.

- Gain diverse perspectives: Seek a wide range of opinions to create products that help a largely dissonant world feel a sense of open, welcoming community.

- Always ask this question: Am I designing a product for social good or could it perpetuate bias?

Design for Good: A Three-part Series

Understanding how to use design skills for social impact, even just on the surface level, is a bit of a meaty topic that covers a chasm of potential for a shift in mentality. Part 1 tackled the dirty underbelly of the power we truly hold as designers to make our work in product design for social good.

Here’s a look at the other two parts of the series:

- Part 2 addresses address social impact design with a discussion on making designs that are accessible and inclusive for everyone, and gaining stakeholder interest in investing in social impact design.

- Part 3 (publishing on Friday, May 24) is a deep dive into some environmental design projects and how we can make our digital work—which is still far from sustainable—more eco-friendly.

The Design for Good series is perfect if you’re a:

- Leader of a design team

Consider how this blog post series could inspire your team to transform their work into a positive impact design career.

- Designer

Challenge yourself to think about these initiatives as a client requirement on every project, rather than waiting for the client to ask for it.

- Student

Or, someone looking for design graduate opportunities—use this series to learn more and grow.

Grow Design Skills at Flatiron

Our UX/UI Product Design Bootcamp offers full- and part-time educational paths for those interested in a career change (or start). You can become a product, UX, UI, or web designer in as little as 15 weeks! Apply today or book a quick 10-minute call with our Admissions team to learn more.