ITT Technical Institute has announced this week that it will shut down operationsfollowing the Department of Education’s decision to bar the for-profit education company—which operates 130 schools across the US—from receiving federal financial aid, including student loans and Pell Grants.

On the heels of the announcement of EQUIP (a new White House initiative Flatiron School is participating in), this move by the administration is another sign of changing attitudes toward education, particularly toward for-profit education companies that have for too long been allowed to continually offer poor outcomes without accountability. The administration is now holding ITT Technical Institute accountable for saddling tens of thousands of its students with significant debt in pursuit of degrees that don’t help them pay off that debt.

In the wake of this news and the developments in the higher education industry, we are republishing our CEO and Co-Founder Adam Enbar’s prescient piece on the biggest issues facing higher education from our recent Quora Session below.

We feel for the thousands of students impacted by ITT Technical Institute’s closure. For some, the alternative education option provided by coding bootcamps like Flatiron School may be the right next step, and we’re pleased to offer a new scholarship specifically for ITT students looking for ways to continue their education: a monthly $500 discount (with total savings of up to $4,000) toward our Online Web Developer Program. Interested students can read more about our program offerings—and independently-verified outcomes—here. If you’re a former ITT Technical Institute student, email admissions@flatironschool.com to inquire about the scholarship.

What are the biggest issues facing higher education in the US today and how can they be fixed?

The biggest issue facing higher education today? Take a look below:

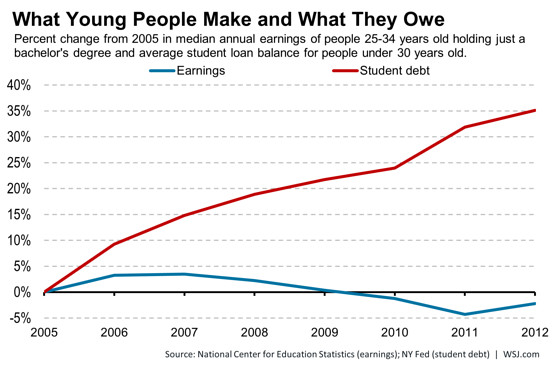

Return on investment. Higher education is becoming increasingly more expensive and it’s not getting results—it doesn’t lead to grads getting jobs that allow them to pay off the debts they’ve accrued from that education.

That’s not to say higher education should solely be judged based on graduate salaries. But even if we consider a liberal arts education as vital because it contributes to your critical thinking skills and makes you a better citizen (people can debate this, of course, but I believe it’s true), we have to consider a few things.

-

We’re not teaching those skills effectively. Take a look at the studies in the book Academically Adrift, which surveyed thousands of students before, during, and after attending college, tracking their learning and critical thinking abilities. The results were largely flat—higher education as it is now didn’t actually improve these skills. So forget about jobs and outcomes. Even the learning we’re claiming is valuable independent of those factors doesn’t actually seem to be happening in practice. If you can’t believe that, if it doesn’t match your experience, consider that if you’re reading this post, chances are you went to a good school, you’re an autodidact, or you’re interested in learning—you’re reading Quora instead of watching Netflix so it’s a safe guess. But for most of America, this is what the data looks like. College doesn’t seem to have the impact we want it to have in terms of that harder to articulate value and experience.

-

Even if done effectively, this sort of education shouldn’t have such a high cost that it destroys your ability to pay off your debts. The purpose of higher education is nothing short of helping people build a better life. As I said, we can debate about the value of simply “being educated” and how that contributes to having a better life. But you can’t argue with the fact that being put into crushing debt without being able to pay it off makes your life much worse. It wasn’t always this way. You used to be able to afford college by working summer jobs. But those days are long gone.

So how did we get here? I’d name two big factors.

Unlimited access to student debt—that’s the giant elephant in the room. By creating a pool of unlimited capital without requiring transparency or accountability regarding outcomes, we’ve bred a lot of bad behavior. There are private equity companies entering the space, realizing they can generate enormous profits by enrolling tons of people for enormous fees. There are easily available student loans without checks and balances. It’s not dissimilar to what happened with the housing crisis—easily attainable capital corrupted by bad actors. You see it all over. As described by the New York Times, George Washington University, lacking rich alumni, built up its reputation by trying to establish the school as a “luxury good,” erecting fancy new building and hiring famous professors. Where did the money come from for these plans? Raised tuitions, which students often pay with student loans. The school’s president is completely candid about the tactics—and George Washington University is just one of many schools doing this. Note that nowhere in the article does he mention using the money to create a better learning experience.

Misguided assumptions about the value of a degree. As a country, we looked at historical data about college performance and determined that it’s a great idea for everyone to go to college. It seemed like based on this data, people with college degrees do better. Even today, this data holds. So we said let’s send everybody to college. It changed the whole culture of education. We started judging high schools and charter schools based on their ability to get people into college.

There’s a big reason this mindset is flawed: these institutions were built for a certain type of student—one who can afford it, one with a certain academic background. And now we’re saying, let’s shove every person into this system even if it wasn’t built for them. It’s like saying “Stanford grads seem to do well; let’s send everyone in the country to Stanford.” Obviously, that’s ridiculous.

When you think about student loan prices, what comes to mind are stories of students with huge $100,000+ in loans, but studies show that the students who often suffer the most from student loan debt tend to be low-income—people taking out smaller loans but later dropping out of college. So they’re left without a degree that might help them get a job that’ll allow them to pay back their debt and they have enormous interest rates on their loans.

We’ve seen firsthand how a one-size-fits-all approach doesn’t work in our fellowship programs here at Flatiron School. When we’ve run our fellowship programs, especially the ones targeting students without college degrees, we’ve had to change our whole approach. Our fellowship students have been no less able from a technical perspective, but we learned that we couldn’t make the same assumptions about them that we make about our students who can afford our tuition. For example, the majority of fellowship students we’ve encountered didn’t know how to apply for jobs. Not because they weren’t smart, not because they didn’t have interview-appropriate things to speak about from their experiences—it’s simply that they had never learned how to apply for something professional. They had never applied for college, they had never applied for a white collar job, they had never have to put together a professional resume. So if we had tried to put these students in the same system as people who had been basically trained their entire lives to apply for things, they would have failed from the start.

And yet, that’s exactly what continue to do as a country. We take people from low-income backgrounds and under-resourced schools and give them scholarships to universities where they are surrounded by people who are generally well-off, who never really encountered adversity, who are able to attend parties instead of working to support themselves. We throw these students into a system not designed for them—without giving them the proper support infrastructure—and we expect them to do just as well the other students. Of course, it doesn’t work out like that.

So, what can we do about these problems? It’s going to be a long road, but I have a few ideas.

Long-term: Reform Title IV. This is a hard problem because it requires an act of congress. And any reform you propose to Title IV (federal financial aid) makes it seem like you’re trying to make college less accessible and the lobbyists will pounce on that. But eventually, Title IV needs to be reformed to require much more transparency and accountability for the aid that’s given.

And furthermore, there needs to be a shift so that people recognize that one-size-fits-all education doesn’t work. Higher education doesn’t have to mean a four year degree; it can come in a lot of forms and people should be able to get an education based on who they are and what will be most valuable to them.

Medium-term: Accountability. Colleges can’t keep operating for years and years taking students’ money without being accountable for outcomes. Public companies have to have their data audited. The government is giving schools a lot of money and they should demand similar accountability: schools and accreditors that don’t meet certain outcomes should not be eligible to give student loans anymore.

Short-term: Forced Transparency. One thing I would do today that could have a giant impact? I’d put a “Surgeon General”-style warning on student loan documents. Before any student signs a loan, they should have to read a giant disclaimer that states they are about to enroll in X major at Y college and shows, for other students who have followed that course of study over the last five years:

-

the percentage of enrolled students who graduated within six years;

-

the percentage currently in default of their student loans;

-

the average amount of student loan debt per graduate.

Certainly full outcomes reporting would be preferred, but this is data that the government already has access to right now. So this could be enacted overnight.

I’m hopeful that changes are coming. We’ve already started to see a remarkable shift in how our country defines higher education through initiatives like EQUIP (Education Quality through Innovative Partnerships), which allows students to use federal financial aid toward certain nontraditional education, such as coding bootcamps like Flatiron School, for the first time—so long as these programs remain transparent and accountable around their student outcomes. This sort of radical transparency is something we’ve been committed to at Flatiron School from day one, and we’re looking forward to seeing more organizations pledge to do the same.