The Case for Accessible Design

Accessible design, defined as design that specifically considers the needs of users with disabilities, seems like an obvious win for designers. Yet many organizations are reluctant to invest in the process of planning, designing, and testing with accessibility in mind. What arguments can designers use to convince companies to prioritize accessibility?

Most designers should already be aware of the importance of accessibility. After all, UX designers spend their careers identifying and removing obstacles between users and their goals. In the case of accessible design, that means testing whether users with disabilities can navigate and understand your content using the assistive technologies they depend upon.

Knowing the principles of digital accessibility is critical for designers. But if you’re the only person at your organization advocating for users with disabilities, your team won’t build accessible products. Accessibility requires a company-wide commitment, an inclusive hiring process that actively seeks the perspectives of people with disabilities, and a structured process of planning and testing. An organization’s accessibility maturity is a measure of the effectiveness and sustainability of its accessibility practices.

Source: The Digital Accessibility Maturity Model

But what happens if you’re at a company with little to no accessibility maturity? How can designers make the case for a product design and development process that prioritizes accessible outcomes?

Case #1: Accessible Design is the Right Thing to Do

Users with disabilities deserve to be able to use your product, and denying them access is discrimination. This is the ideal reason organizations should embrace an accessible approach.

Any designer who truly values usability should understand that no product is truly usable until everyone can use it. This definition absolutely includes users of assistive technologies.

While there are numerous types of assistive technologies used to navigate the web, some of the best-known tools include:

- Screen readers: software that reads web content aloud to assist users who are blind or have low vision

- Screen magnifiers: software that increases the size of text and other web content for users with low vision

- Alternative input: some users are unable to operate a mouse or keyboard, and depend on alternate methods of controlling the computer, such as:

- Voice recognition: Users provide commands to the computer verbally

- Eye tracking: Users control the mouse pointer via eye movements and blinking

- Switch controls: Users with limited mobility can navigate computers using, for example, switches controlled by pressing a button or by the user’s breath

Disability and accessibility expert Sheri Byrne-Haber recommends showing team members numerous assistive technology demonstrations when advocating for accessible solutions, which presents users of assistive technology as highly capable once usability barriers are removed.

Accessible Design Supports All Kinds of Disabilities

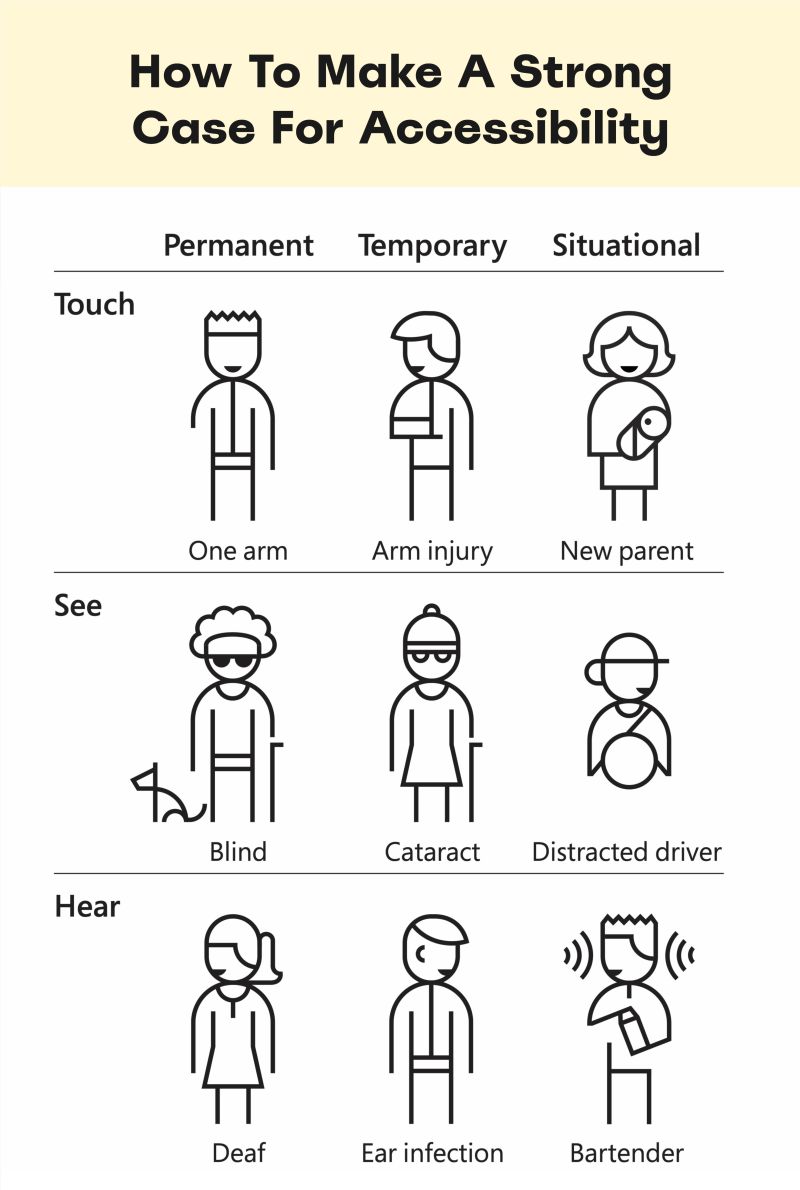

As Microsoft’s Inclusive Persona Spectrum makes clear, accessible design doesn’t only support users with permanent disabilities. Some disabilities are temporary, affecting the user for a limited time. Temporary disabilities might result from illnesses, injury, or surgery.

Other disabilities are situational, meaning the user’s abilities are impacted by specific, short-term circumstances.

Captions, for example, make audio and video content accessible for all of the following:

- Users with a permanent disability such as deafness

- Users with a temporary disability such as an ear infection

- Users with a situational disability such as working in a noisy room

Accessible Design Improves Usability For All Kinds of Users

The usability benefits of accessible design frequently extend to all users. This phenomenon is known as the curb-cut effect.

It may seem difficult to imagine a modern city without ramps cut into sidewalks to provide access for people in wheelchairs, but disability activists fought for decades for the right to usable sidewalks. Curb cuts specifically benefit people in wheelchairs, but they also make access easier for people pushing strollers, rolling luggage, or using crutches.

Returning to our example of captions for audio content, while statistics suggest that 15% of US adults have some degree of hearing loss, 50% of Americans watch videos with subtitles most of the time. So while captions are a must for deaf users, they also assist other viewers, including:

- Users who aren’t native speakers of the language used in the video

- Users watching the video at a low volume or in a noisy environment

- Users who use captions as a concentration aid

Case #2: Accessible Design is Good For Business

In June 2020, Twitter experienced a public relations fiasco when it released an inaccessible audio tweets feature without captions. The company admitted it lacked a full-time accessibility team that would have caught the issue during the planning and testing phases, and more than a year passed before Twitter finally launched accessible voice tweets.

While the ethical argument outlined in the previous section of this article still applies—Twitter needed higher accessibility maturity because providing audio content without captions discriminates against users who depend on them—the bad publicity surrounding the inaccessible audio tweets also undoubtedly harmed Twitter’s reputation as a company. How can designers make a business case for building accessible products?

Accessible Design Increases Market Reach

The United Nations estimates that 15% of the world’s population lives with a disability. That number rises to over 46% for people 60 years and older.

In the United States alone, there are approximately 20 million working-age adults who report at least one disability, with a market share of about $490 billion.

In addition to enhancing your organization’s reputation as disability-friendly, building accessible products means people with disabilities can spend their money at your business and not somewhere else. And customers with disabilities are frequently highly loyal; due to the difficulty of finding accessible accommodations, for example, disabled travelers tend to find one solution and stick to it.

An accessible website is also easier to find using search engines, thanks to the SEO benefits of semantic HTML markup and accessible media content. Google and other search engines value accessibility best practices such as:

- descriptive and properly ordered headings

- descriptive link text

- alternative descriptions for images

- captions and transcripts for audio and video files

Accessible Design Can Lower Operational Costs

If users with disabilities are able to conduct successful transactions using your product, that means fewer complaints, which lowers the amount your business needs to spend staffing customer service centers.

Accessible Design Leads to Innovation

A common misconception about accessible design is that accessibility compliance stands in the way of the creation of innovative products, when in fact much of the technology users currently rely upon for communication was originally invented to help users with disabilities, including the following:

- Keyboards: typewriters with keyboards were initially invented in the early 19th century to help blind people compose letters

- Transistors: the first transistorized consumer product in the US was a hearing aid

- Captions: Captions first appeared on TV in the 1970s to assist viewers who are deaf and hard of hearing

- Email: Vint Cerf, who helped create the first email service connected to the internet as well as the TCP/IP protocol, sees email as a powerful communication tool for hearing-impaired users like himself

- Multitouch interfaces: A graduate student battling carpal tunnel syndrome developed the multitouch technology powering the 2007 launch of the iPhone

Case #3: Accessibility Compliance Avoids Lawsuits

Avoiding lawsuits isn’t the ideal motivation for an accessibility program, as it tends to lead to doing the bare minimum, reactively conducting audits and applying fixes rather than proactively building a sustainable level of accessibility maturity.

Still, if the ethical and business cases for accessible design don’t sway your organization, perhaps the very real threat of a lawsuit will.

Accessibility Lawsuits are Increasing, and Quick Fixes Aren’t Helping

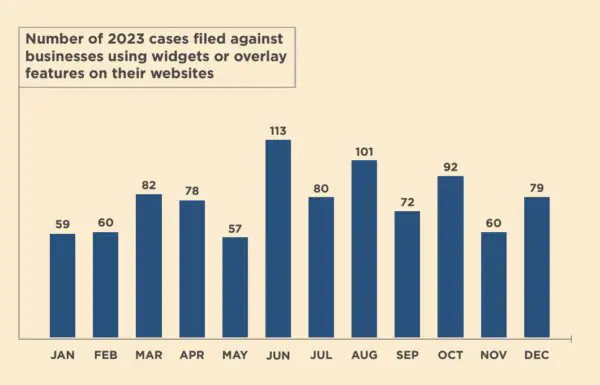

From 2019 to 2022, the number of website accessibility lawsuits filed in federal courts annually increased from 12 to 14%. By 2023, the total number of lawsuits had climbed to more than 4,600.

What’s striking about the 2023 numbers is that over 900 of the lawsuits were against businesses that included accessibility overlays on their websites.

Accessibility overlays are automated plugins that attempt to improve a website’s accessibility through external third-party code. While these overlays promise a quick fix, thus far they’ve proved no substitute for a robust accessible design process. In fact, a blind user named Patrick Perdue told The New York Times in 2022 that overlays make using a screen reader to navigate the web more difficult:

“I’ve not yet found a single one that makes my life better . . . I spend more time working around these overlays than I actually do navigating the website.”

Solving For Accessibility is Cheaper Than Settling a Lawsuit

According to attorney Kris Rivenburgh, businesses targeted in web accessibility litigation can expect to spend a minimum of $25,000 in legal fees and remediation expenses. And the costs can sometimes be far higher.

In the court case Robles v. Domino’s Pizza, LLC, a blind user named Guillermo Robles sued Domino’s Pizza because its website and mobile app were not accessible using a screen reader. The pizza chain spent six years in court arguing unsuccessfully that the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) should not apply to websites.

By the time the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals confirmed in 2022 that websites qualify as “places of public accommodation” and deserve ADA protection, observers estimated that Domino’s had spent millions of dollars in legal fees. And by fighting the lawsuit, Domino’s established a reputation as a brand willing to discriminate against users with disabilities.

Most organizations would prefer to avoid serious legal fees and a similar hit to their reputation. The best strategy to avoid lawsuits is a high level of accessibility maturity—one you can advocate for as a compassionate and informed designer.

Interested in Designing for Accessibility?

If designing products that people with disabilities can use aligns with your passions, consider applying now to Flatiron School’s Product Design Bootcamp. Our curriculum contains numerous lessons on working accessibility into your design process and complying with accessibility guidelines.

Not sure if you’re ready to apply? Download the syllabus to learn more about the skills you can acquire in our bootcamp.

And if you are curious about what students learn during their time at Flatiron, attend our Final Project Showcase.

Disclaimer: The information in this blog is current as of April 6, 2024. Current policies, offerings, procedures, and programs may differ.