Where there’s a problem, there’s a solution. And where you’ll find answers, you’ll find agents of change helping to shape the world and make it a better place. Dr. Nimmi Ramanujam, the Robert W. Carr, Jr., Professor of Biomedical Engineering at Duke University and Director of the Center for Global Women’s Health Technologies, has dedicated her career to addressing gender inequities in STEM education and sexual and reproductive health, which she sees as two sides of the same coin.

Dr. Ramanujam is the Grace Hopper Celebration’s 2019 Social Impact Abie Award winner and we’re proud to sponsor this incredible award. For Dr. Ramanujam, this award is a way to continue to support women and to create change on a global level.

In her career as a biomedical engineer, Dr. Ramanujam has used technology as a powerful tool to solve a global problem. “As a researcher and engineer I started working on inequities in cervical cancer,” she says. “The disease is completely preventable and half of the women affected are in the prime of their life. And, unfortunately, many of these women are women of color, from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds, and many of them are from low and middle income countries.”

She began thinking about the root of the problem and identified two primary concerns. First, governments and practitioners are providing solutions that work, but aren’t reaching the women who need them, according to Dr. Ramanujam. Secondly, women either don’t know these solutions exist or are afraid of an exam and the diagnosis. “A large part of these gaps in sexual reproductive health have to do with an unempowered individual who follow social norms that don’t encourage action and good health,” Dr. Ramanujam says.

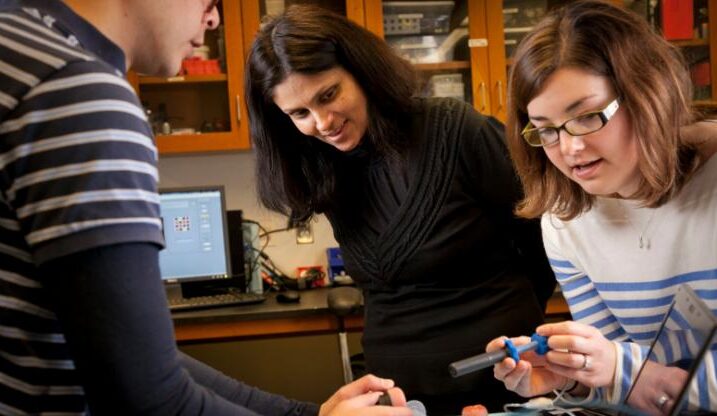

That’s where tech can play a role. “Technology that can solve the public health problem and give women the agency to take ownership of their bodies and their tests,” she says. Dr. Ramanujam and a team of female inventors did just that with the Pocket Colposcope and its companion technology called the Callascope. Together, they built a device that brought the care to where women in need live.

Thinking about the problems related to cervical cancer, Dr. Ramanujam started thinking about all the other problems related to sexual and reproductive health. She also began thinking about who was helping to solve these problems and the answer was women innovators and inventors.

In fact, one of the women on the team that developed the Callascope, Mercy Asiedu, is from Ghana and went back to her home country and implemented the technology, just this year. “She’s a great example of a woman who mirrors the society that she’s innovating for and close that circle,” she says. “But, she shouldn’t be the exception. She should be the rule.”

Dr. Ramanujam readily admits to using the late Anita Borg, whose organization hosts the Grace Hopper Celebration, as the inspiration for her mission. She jokingly says she plagiarized the phrase in Borg’s mission statement to describe what she and her team are striving to do “create solutions by empowering people that mirror the societies their serving.”

Through her work, Dr. Ramanujam saw an opportunity to bring women’s issues to the forefront and bring women to the table to solve the problem. “Anyone can solve these problems. You just need passion and perseverance,” she says. To realize this vision, she founded Ignite, an educational initiative, to help find solutions to community problems that girls in the least-resourced parts of the world face (lack of access to lighting and clean water for example) and use STEM education as a way to to think about these inequalities and ideate solutions for them.

She’s seen a groundswell of women and trainees, engineers and non-engineers doing STEM. Except, she doesn’t call it STEM. “We call it ‘social innovation’ for the greater good,” Dr. Ramanujam says. “Students from different countries, underrepresented groups, boys and girls, come together to solve problems to create a healthy working environment.”

By focusing on the problem itself, you avoid some of the stigma or barriers that have been built around STEM education that have prevented women from entering the field. Dr. Ramanujam wants people to figure out where these barriers are, create a narrative that they can relate to, and contextualize the problem in ways that make sense to them. “The beneficiary becomes the benefactor and lets them — women receiving the care or the technologist inventing the solution — reframe the problem and solution in their own terms. That creates ownership and that creates advocacy,” Dr. Ramanujam says.

You’re still teaching STEM, but it’s through the lens of trying to solve a problem. In her Ignite program, women find a problem that they are directly impacted by and are taught ways to solve that particular problem. To date it has involved access to clean water or electricity in a low-income community and technology is a means to an end but there are so many more challenges and perhaps the beneficiaries could develop the next-generation curricula creating a virtuous cycle in their own communities.

Her advice for anyone looking to enter STEM is to find something that matters to you. “Start with what you like and how that can help solve a problem. If you don’t know, talk to people. There’s nothing better than community. You can’t do this alone.”

If there are no mentors or community, create one. Be the change that helps communities and society grow.

At the Grace Hopper Celebration, Dr. Ramanujam is excited to speak to over 20,000 women. It’s the first time she can do that in her career as an engineer, having an audience of mostly women. “Being able to share that moment with so many women will be incredible,” she says.

Flatiron School is proud to be a part of the Grace Hopper Celebration and hope to see you there!