The following is a guest post by Max Jacobson and originally appeared on his blog. Max is currently a student at The Flatiron School. You can follow him on Twitter here__.

I’ve been using this Octopress blog for a couple weeks and I’m compelled to figure out how it works and came to be. Let’s spelunk now.

In October 2008, in a blog post called “Blogging Like a Hacker” Tom Preston-Werner (GitHub co-founder) announced Jekyll, a new website generator for his personal blog. He sought to answer the question: “What would happen if I approached blogging from a software development perspective? What would that look like?” Here’s the wayback machine archive of that post which is remarkable mainly for looking pretty much the same.

A scant two months later, in December 2008, GitHub announced Pages, a new way to host static sites on GitHub, each of which is processed by Jekyll, regardless of whether the programmer took advantage of its features. (Sidebar: it would be fun to work at a company where I could have an idea for a personal project and then find a home for it in a place that others will find and get use from it.)

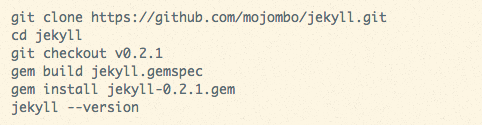

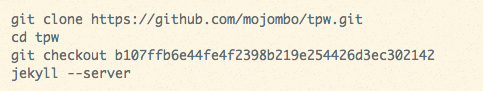

At that time, Jekyll was at v0.2.1. In order to time travel and try that version of Jekyll on my local machine I ran these commands:

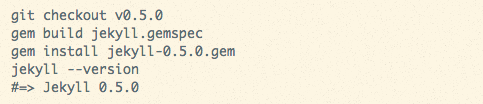

And got a bunch of error messages. Ok. I don’t know what’s up with these. Let me fast-forward to April 2009 when they announced that GitHub pages was upgraded to use Jekyll v0.5.0. The marquee feature of v0.5.0 is a configuration file.

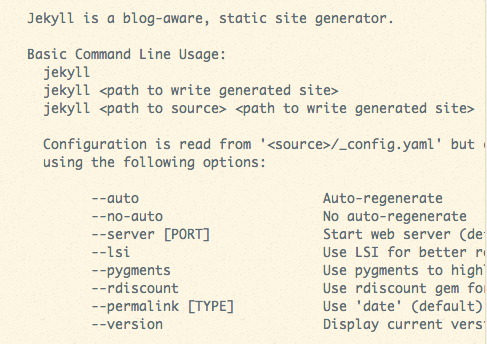

OK nice. I’m close to arriving at a point. Imagine being a programmer wanting to start a blog at this point in time and wanting to write in Markdown or Textile and wanting to manage your source files in Git and compile a static site and deploy it on GitHub and encountering this upon running jekyll --help:

Alright, cool. Yeah. Ok. Wait where do I start?

Real blog agenda confession: I was planning to get stumped here to make a point but actually the README pretty clearly recommends cloning a “proto-site repo” at https://github.com/mojombo/tpw and going from there so that’s what I’ll do now and see where this takes me.

(That SHA is the last commit to that repo as of April 2009 and I feel like a time traveler with secret codez).

What this gives you is a blog that looks very much like Preston-Werner’s and a pattern to follow: replace his posts with your posts; replace his name with your name; commit and push. Now you have a stark, white blog just like that cool guy.

Later in 2009, in October, Brandon Mathis released Octopress, a framework for Jekyll. In what must be an homage to that original blog post, its tagline is “A blogging framework for hackers”. Since then he’s built an ecosystem for plugins and themes around this framework. Where Jekyll is “blog aware”, Octopress is blog obsessed. Where Jekyll gives you just enough to get started, Octopress gives you a super sturdy, robust design and toolset.

Some key differences between Octopress and pure Jekyll

-

When deploying an Octopress blog to GitHub Pages, you compile the static files before pushing; when deploying a pure Jekyll blog to GitHub Pages, you push the uncompiled source files, with unrendered markup files and templates, and it compiles the assets upon receiving the push. If you want to use plugins, Octopress is a better choice because their effects can be wraught during the compilation but not in the post-receive hook (on GitHub anyway; you can set up your own server if you need all that).

-

That also means you only need one branch for a pure Jekyll blog, where you need two (“source” and “master”) for Octopress.

-

It also means the commit log on your master branch is full of auto-generated, non-semantic commit messages (_boo_right?)

-

There are way more source files in an Octopress blog, which can feel somewhat constrictive, at least to this young blogger.

-

Octopress’s

rake previewcommand watches for changes, including those made to the sass files, and compiles those into CSS. It would be cool if it compiled CoffeeScript too. -

Octopress has this kind of confusing relationship with Git branches where its root directory stays on branch “source” and is updated by the blogger, and contains a directory called

_deploywhich contains a second instance of the same repo, which is meant to stay on branch “master” and be auto-generated by the framework. It’s a clever solution to the situation constraints but not immediately intuitive or adequately explained (including by me just now, I’m sure).

Because Jekyll is distributed as a gem and has a simpler, smaller file structure and a normal git repo, I’m tempted to suggest it’s a better place to start for someone interested in getting their feet wet with this kind of “hacker” blogging. It’s easy to discard Preston-Werner’s theme and start from scratch, and if your site is ugly then, as we’ve learned, you’re in good hacker company.

This is probably more true than ever since, in May 2013, just last month, Jekyll 1.0 was released and with it a magical, long-overdue command: jekyll new which — you guessed it — instantiates a plain white blog for you on your filesystem.

Also new is http://jekyllrb.com, some great (and beautifully designed) documentation to reference as you extend your site.

what even is jekyll

The Jekyll program itself is written in Ruby, but you don’t need to know Ruby to work with Jekyll. You just need to be okay with the idea of Ruby code generating your blog. In fact, if you go in knowing some Ruby, you might find yourself confused by some things like I was.

Jekyll looks at each markup file (HTML, Markdown, Textile) in your project and looks at the file extension to know how to convert to HTML, if it needs to. It’s smart enough to know that some people use .md and others use .markdown and to just be chill about it. It reads the “YAML frontmatter” to look for instructions for what to do with these files, like if it should look like a post, with the date and maybe comments or if it’s just some generic page. You can stash arbitrary values in their to use in your layouts too, like putting mood: happy at the top of fun posts and then referencing page.mood in your posts layout.

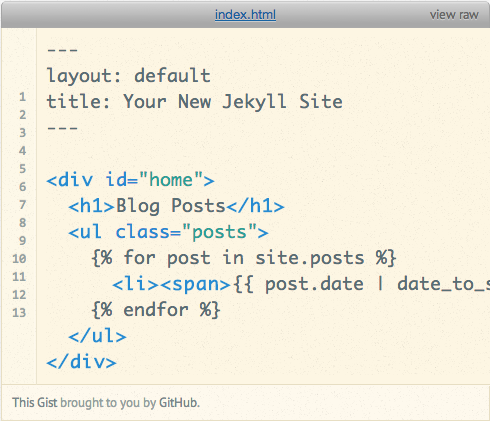

So let’s talk about that templating system briefly. Knowing Jekyll is a Ruby project, and having dabbled with Ruby web development, I made the mistake of assuming Jekyll would follow Ruby conventions that I was familiar with (something like Haml or ERB or Slim), but it kind of doesn’t. What it uses is Liquid, a templating system developed by Shopify. Like Jekyll, it’s written in Ruby and distributed as a gem, so it bundles along well. Once I adjusted my expectations, I found it easy to work with. When you initialize a new Jekyll site (with jekyll new my_great_blog), it gives you this index.html file to be your barebones homepage:

(note: I think I have to use a GitHub Gist to host that code snippet because if I embed it in this post, Jekyll will interpet the Liquid tags)

Alright so clearly it’s mostly HTML, and the file extension is .html, but there’s a lot in there that’s not valid HTML and would confuse your browser if opened directly. Which is fine, because that’s not what you do. This is what a Liquid template looks like. If you’re looking for Ruby, you’ll be rebuffed by this. I have no idea where endfor comes from and the double curly braces and dot notation are very JavaScript-y. So learn to love Liquid, I guess.

This file is not a complete web page. It has no doctype or <head> or <body> tags. It’s a partial. The file that has the rest of it is in _layouts/default.html and the line layout: default in this file tells Jekyll to compile this, then insert it into that. You can define more layouts but you may not have to. The other layout that comes with Jekyll is _layouts/post.html which is actually also a partial. When you write a blog post, it has layout: post in the YAML, so the compiled post is sent to _layouts/post.html, which has layout: default in the header, so it does a few things then passes the ball along to its final stop. It’s like a cheap Russian nesting doll with only three dolls.

unspelunk

Honestly both are great. Octopress feels like rocket powered training wheels, but that’s a fun visual so